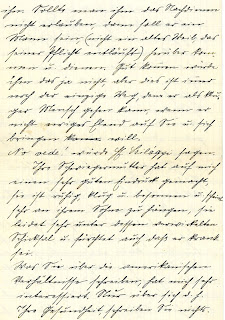

Jickeli Household Help. Lisi Ebner seated 2nd from left. Mrs. Jickeli, center in black.

|

On Jan. 23, 1943, my uncle, Frank Ebner Gartz, (photo in uniform, above) reported to the draft board in Chicago to start his training for WWII. So began the correspondence between him and family & friends, comprising almost 300 letters going both ways. I’m posting many of these World War II letters, each on or near the 70th anniversary of its writing. To start with his induction, click HERE.

This blog began in Nov., 2010, when I posted a century-old love note from Josef Gärtz, my paternal grandfather, to Lisi (Elisabetha) Ebner, my paternal grandmother, and follows their bold decision to strike out for America.

My mom and dad were writers too, recording their lives in diaries and letters from the 1920s-the 1990s. Historical, sweet, joyful, and sad, all that life promises-- and takes away--are recorded here as it happened. It's an ongoing saga of the 20th century. To start at the very beginning, please click HERE.

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Hidden Message Behind Women's Work

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

An odd fellow-missing World War I

|

| World War I trench warfare photo credit: www.anunews.net/blog |

These family photos were taken at the same time that Europe was engulfed in the nightmare of World War I, and most young men of Josef's age (25 in 1914) would have been covered in lice, crouching and rotting in some trench, being blown up or blowing up other young men.

My grandmother’s brother, Samuel, was one of those young men (See The Fallen-Part I).

|

| Gartz Family ~ 1915-1916 L-R Lisi, Will, Fred, Josef |

|

| Military Draft Notice, Josef Gartz Austro-Hungary |

But the first year after Lisi and Josef had married in Chicago, my grandmother’s former employer, Mrs. Jickeli, saw only youthful indiscretion in their decision to emigrate to America. Two months after Lisi and Josef married in Chicago on October 13, 1911, Mrs. Jickeli had written Lisi Ebner a letter expressing her dismay at Lisi's hasty departure to join her love, Josef Gärtz. She had chastised them both for their impetuous behavior and a host of issues, even declaring their marriage wouldn't be considered valid in their homeland Siebenbürgen (because it hadn't been announced in the church).

She reiterated her concerns in a second letter, three months later, in what today we might say was “beating a dead horse," even if a stick of a slightly different length!

|

| Merchant's wife, Berta Jickeli born Henriette Albertine Krasser |

My Dear Lisi,

Are you satisfied with your home (apartment)? Have you been employed long and how does Gärtz like the cooking spoon? [Josef was working in a restaurant when Lisi arrived]. That you live in peace makes me happy. I have certainly never doubted that Gärtz seems like a good man (Mensch). I have always considered him to be a good and respectable/honest/decent man, but a bit of an odd fellow.

But you also know that I am too old and have seen too much of life to scream “Hurrah!” A happy marriage is very rare in life and to be sure, even more rare because no one holds his fate strictly in one’s own hands and no one knows what tomorrow brings. Besides that, marriage seems different after 10-20 years than in the first year. That you will experience, just as everyone has. For you and Gärtz it’s just that you went into your marriage so fast and with such impatience.

You will have to go through double the work and sacrifice and homesickness than you would have endured if you had waited one more year. Even our Lord God cannot reverse your fate. First Gärtz will have to comply with his military duty if nothing changes. Without you coming here, for the time, then the second thing that has to be is that your marriage must also be declared binding here. This is the only way a later happiness can bloom.

Mrs. Jickeli ends her letter with a few paragraphs of local news and heartfelt wishes, for after all, she was like a second mother to Lisi, and sincerely worried for her.

And now, dear Lisi, I wish you both very well, and don't grow tired before you again have a strong foundation under your feet. We all greet you both from our hearts, and I remain for all time––Your old mother

Berta Jickeli

Berta Jickeli was right in one regard: people certainly don't have complete control over their fates, as all those who've been caught in war know so well. Yet Josef had influenced his fate, and the fate of his family, through his determination to get to America. The letters make it clear that friends and relatives back in Siebenbürgen/Transylvania expected he and Lisi would return. They didn't know Josef very well.

So when another serious problem emerged back in Transylvania after Josef left for America, his swift decision to leave his countryland again appeared to those back home to have been foolhardy. Apparently some local person had taken advantage of Josef’s departure, perhaps in cahoots with a local official, and co-opted from Josef his home and land. Both Lisi's father and Mrs. Jickeli weighed in on what had happened. Coming up next time at Family Archaeologist.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Hidden Message Behind Women's Work

|

| Jickeli Household Help. Lisi Ebner seated 2nd from left. Mrs. Jickeli, center in black. |

Women’s work: peeling potatoes, mixing ingredients, grinding meat, baking (a large container labelled “Zucker” [sugar] sits on the table), cooking, spinning, knitting, washing, and ironing [two irons were used, one heating on a stove to be switched out with the the one in use when it cooled off]--all tasks necessary to keep a household running smoothly in the early 20th century.

My grandmother, Lisi Ebner, is seated second from left, whisking up something in a bowl. In the center, dressed in black, is Berta Jickeli, the employer of the women in the photograph. It’s hard to see, but she’s holding knitting needles in her hands. My grandmother adored Mrs. Jickeli, as she always called her, and was devoted to her daughter, Lisbeth [LIZ-bett], the little girl at the washtub, for whom she was governess.

Uli, the professor whom I met on the 2007 roots-finding mission, told me that the Jickelis were a prominent and wealthy family in the area. Mrs. Jickeli’s husband, Carl Friedrich Jickeli, owned a large hardware store in the center of Hermannstadt. Their children were educated and accomplished. Mrs. Jickeli’s nephew, her sister’s son, was Hermann Oberth, known as the “father of rocketry/space travel.”

Clearly impressed, Uli asked how my grandmother obtained such an excellent position. “She was smart, loyal, and had an abundance of focused energy,” was the answer I knew to be true.

After she left for America, Lisi corresponded with Mrs. Jickeli for more that forty years and with Lisbeth for more than 60 years. She saved every letter, and through them I’ve come to understand the love they shared for each other and how much Mrs. Jickeli depended on Lisi’s intelligence and devotion. The letters are a chronicle of these European women's lives through the first half of the 20th Century and a first-person view of the devastation visited upon my grandparents' homeland in the aftermath of two wars.

A few months ago I removed the photo from its frame to make a digital copy. On the back, hidden for 100 years, was an inscription and date! I discovered for the first time that this photo was a gift to Lisi from Mrs. Jickeli, inscribed with two verses (more like aphorisms) that undoubtedly were intended to help guide Lisi through life. (I later learned the verses were written by Georg Scherer, 1808-1909).

Kommt ein Lichtgedanke dir,

Laß ihn nicht entschweben,

Eh` du ihm die helle Zier

Klarer Form gegeben.

Und wenn auf dem Pfad der Pflicht

Dir ein Leid begegnet,

Ring mit ihm und laß es nicht,

Bis es dich gesegnet.

If a clever thought comes to you

Don’t let it disappear

Before you share it with others.

And if on the path of duty

You still have troubles

Wrestle with them; don’t allow them [to get you down]

Until you turn them into blessings.

In other words, share your good ideas, and when life is hard, don’t give up. Endure! Fight against your troubles until you can find some good in them. It’s a philosophy that would serve my grandmother well as as she struggled to make a new life in a foreign country.

In the bottom right hand corner, Mrs. Jickeli signed the photo with the following message:

It was the first time I learned the date of this iconic photo, a century after it was taken. Perhaps Mrs. Jickeli realized that Josef would be leaving soon for America, that Lisi might soon follow, and gave her this photo as an early farewell gift.

In fact, Josef would leave sooner than anyone expected, and he and Lisi would never spend another Christmas together in their homeland.

Merry Christmas - 2010

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Can Love last 100 years? November 18, 1910-November 18, 2010

I can see it in this postcard, mailed one hundred years ago today, November 18, 1910, by Josef Gärtz to his sweetheart, Elisabeth Ebner (ABEner) to celebrate her Name Day. Josef was twenty-one. Elisabeth was twenty-three. Within a year they would marry and eventually become my grandparents.

But I didn't always know about the love expressed in language as flowery as the blue-bedecked bicycle pictured on the front. In fact, before last year, I didn't know this postcard existed.

It was one of scores of missives my grandmother had saved for almost seventy years. "Trash or treasure?" My brothers and I debated, in a frenzy of sorting after my mother's death. We squinted at the illegible writing, written in an ancient German script that most present-day Germans can't read much less a German major like me. We decided to keep them, but I figured they'd languish for years in "Box 14, Gartz Correspondence" and end up summarily tossed.

Enter fate.

My brothers and I traveled to Transylvania in 2007 on a family roots-finding mission. In Sibiu (called Hermannstadt by the Germans), we met Professor Uli Wien who was researching the history and immigration of Siebenbürgen Germans -- people like our grandparents. Uli asked for our email addresses.

Serendipity had begun its subtle work.

I forgot all about Uli until the summer of 2009, when he emailed me. “Do you by any chance have any letters to or from your grandparents?”

Did I have letters! My heart leapt at what this meant. Perhaps Uli could help me decipher the inscrutable writing! That put me on a mission to look at the letters closely for the first time in the fifteen years since Mom's death -- and I began to tease out some authors' names.

F[räulein]Elise Ebner

Reisper Gasse [Street]

c/o Mr. Ji[c]keli [the family my grandmother worked for]

Hermannstadt

Nagyszeben

(yet another name for Hermannstadt / Sibiu: Nagyszeben is the Hungarian name)

I recognized my grandfather's signature: “Josef Gärtz," and I knew I had a treasure.

Printed under the bicycle on the front:

Herzlichen Glückwunsch zum Namenstag. “Heartfelt Good Wishes for your Name Day."

I sent a xerox of the writing to Uli, and he deciphered into modern German those words written one hundred years ago today. I translated Josef's sincere, flowery note into English, its tinges of 19th century formality not diminishing its sweetness:

Yours faithfully,

J[osef] G[ärtz]

Neppendorf, November 18. 1910"

I know love when I see it.